Morgan Memories – Capture of James Morgan, Jr.

Major General James Morgan, Jr.’s Rifle, Musket and Powder Horns. Image courtesy of his descendants George Morgan Bown and Alison Bailey.

In scanning various sources relating to the history of the Morgan family, property, and areas surrounding the property over these past 8 years, I kept running into the occasional reference of Captain James Morgan, Sr. and Sergeant James Morgan, Jr. having been captured by the British where “Captain Morgan made his escape through the heroic efforts of the son…” Not wanting to perpetuate myths, this web site does its best to only provide documented facts vs. perpetuating folk lore without identifying it as such. Thanks to a number of people, a reputable source has been identified which not only provides information about this specific event but also confirms other suppositions surrounding James Morgan, Jr.’s capture.

Major General James Morgan, Jr.’s Musket Horn with Image of General George Washington. Image Courtesy of His Descendants George Morgan Bown and Alison Bailey.

During the American Revolutionary War, and subsequent to it, various pension acts for Revolutionary War Veterans were passed. Section 2 of one of these acts, dated February 3, 1853, slightly changed the terms of a prior act:

That the widows of all officers, non-commissioned officers, musicians, and privates of the Revolutionary army, who were married subsequent to January, anno Domini eighteen hundred, shall be entitled to a pension in the same manner as those who were married before that date.

Three years after his first wife, Catherine Van Brockle died (Jan 27, 1802), James Morgan, Jr. married his second wife, Ann J. Van Wickle, on October 20, 1805 in Cranbury, NJ. He was 48 years old at the time and she was 31. Ann was the daughter of James’ one time commanding officer Simon Van Wickle and Simon’s wife Ann Van Cortlandt. It is interesting to note that Ann Van Wickle wasn’t even born until just after the war ended! The Treaty of Paris, ending the war, was signed on September 3, 1783; the paperwork had to work its way across the Atlantic twice (at the time, a minimum 4 week journey each direction) until it was fully ratified on May 12, 1784. Ann was born 3 days later on May 15, 1784.

Years later, on December 26, 1853, 70 year old Ann Morgan personally appeared before the Inferior Court of Common Pleas – undoubtedly located in nearby New Brunswick – to give a declarative oath,

… in order to obtain the benefits of the provision made by the act of Congress, passed on the 3rd of February, 1853, granting pensions to widows of persons who served during the Revolutionary war.” At the time Mrs. Morgan was, “a resident of the Township of North Brunswick, in the County of Middlesex and State of New Jersey.

As of the time of this writing, the location of the house Ann Morgan lived in in 1853 is known as Tanner’s Corner and is located in present day South River, New Jersey – right on the border of East Brunswick (which separated from North Brunswick in 1860). The house faced Main Street in the triangle formed by Old Bridge Turnpike, Hillside Avenue and Main Street. Now there is a gas station and bar/store in this triangle.

The Inferior Court was likely located in present day downtown New Brunswick, a journey of some 7-8 miles from Mrs. Morgan’s home. While a trivial distance today, it would have been a multi-hour trip in both directions by horse and buggy in 1853.

The gem contained within Mrs. Morgan’s oath relates to her husband’s ordeal in late 1777:

That she is the widow of Lieu. James Morgan, Junior, who was as she believes an orderly Sergeant, in the company of New Jersey Militia, of the Revolutionary War, commanded by his father James Morgan; That after having served some months as such Sergeant as aforesaid, he and his father Captain James Morgan were with many others taken prisoner by the Brittish; that through the efforts of her husband, the said James Morgan Junior, his father Captain James Morgan escaped both captivity and death, for which he (her husband) was felled to the earth by a blow on his head and face, which for a time disabled him, and produced a large scar which he carried through life;

I had not previously seen any reference to “a large scar which he carried through life” on James Morgan, Jr’s face. He would have been age 20 at the time of his capture.

He was carried a prisoner to the Old Sugar House in New York, soon after he was taken as above stated, which was at Cheesequakes, in the Township of South Amboy, Middlesex County, New Jersey, toward the close (as she believes) of the year 1777; That he remained a prisoner a full year much of the time heavily ironed; the British refusing to exchange him because of his daring and bravery;

Much like as will occur a few years later with the death of James’ brother, Nicholas, here again is a reminder that the Revolutionary War didn’t just happen far away from Morgan but actually occurred in and around Morgan. Prior to its modification in the early 1880s, the mouth of Cheesequake Creek was originally located right where modern day Route 35 crosses over the NJ Transit Railroad tracks. While it isn’t clear where “in Cheesequakes” James Morgan, Jr. was captured, it could have been anywhere along the creek much of which borders the southern part of Morgan.

Louis Oram, Livingston’s Sugar House, 1830. Livingston Family’s “Old Sugar House” is on the left and the Middle Dutch Church is on the Right. Looking Toward the South Side of Liberty Street (Previously Crown Street). From the Collections of the Museum of the City of New York. Retrieved from http://collections.mcny.org/Collection/Livingston’s-Sugar-House-2F3XC5GYBIS.html

The Old Sugar House.

Were you aware that more American soldiers died while prisoners of the British during the Revolutionary War than did on the battlefield?

In the days a century and a half before the “Geneva Convention” – often quoted in World War II movies and officially known as the “Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Geneva July 27, 1929”, treatment of Prisoners of War was typically more brutal – if you can imagine that. During the American Revolution, it was even worse as we’ll soon see, partially due to King George III of Great Britain declaring in 1775 that those captured were to be considered as traitors, not prisoners. The American colonies were part of Great Britain and its populace were British citizens. Declaring American colonists captured in the conflict as “Prisoners of War” would have meant that Great Britain was acknowledging America as an independent nation. That wouldn’t do, indeed.

Estimates of American colonists who died in action during the entire Revolutionary War period are around 6,800 – just over twice the number of people killed on one day, over 200 years later, on September 11, 2001 in lower Manhattan Island. Estimates for those who died while prisoners of war during the revolution range from 8,000 to 12,000 primarily due to starvation or disease.

Right after they took possession of New York City (i.e., Manhattan Island known then as “York Island”) on September 15, 1776 – just after the Battle of Long Island, the British used two primary methods to house prisoners per the orders of British General Sir William Howe: existing buildings many of which were on Manhattan since New York City was a British stronghold throughout the conflict, and ultimately, at least 16 ships moored in Wallabout Bay (the bay fronting the Brooklyn Naval Yard between current day Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges).

Ships provided a convenient way to instantly increase capacity along with a built-in way to make it not easy or, indeed, possible to escape.

Both types of prisons produced their own respective notorious examples of inhumane treatment of prisoners (or traitors). In Wallabout Bay, the hulk of what would ultimately become the infamous ship HMS Jersey, built in 1736 and most recently used as a hospital ship before hostilities began, was converted to a prison ship. During the course of the war, many thousands were interned on it and many thousands died on it.

On land, there was neither time nor resources available to quickly build facilities in which to house the 1000’s of prisoners already in custody. Most of Manhattan Island in the late 1770’s, excluding the southern most part, the portion nearest the Atlantic Ocean, was, as per David McCullough in his book, 1776, “a mix of woods, streams, marshes, and great rocky patches interspersed with a few small farms and large country estates….” At least three families (Livingston, Rhinelander, and Van Courtland) had warehouse buildings in the southern portion of Manhattan near the docks which were used to store and perhaps process rum, sugar or molasses imported from the Caribbean. These types of warehouses were naturally known as “Sugar Houses” but apparently also had all the necessary attributes which easily lent them to being places to incarcerate people. And thus, the British military commandeered these Sugar Houses to incarcerate the rebel prisoners.

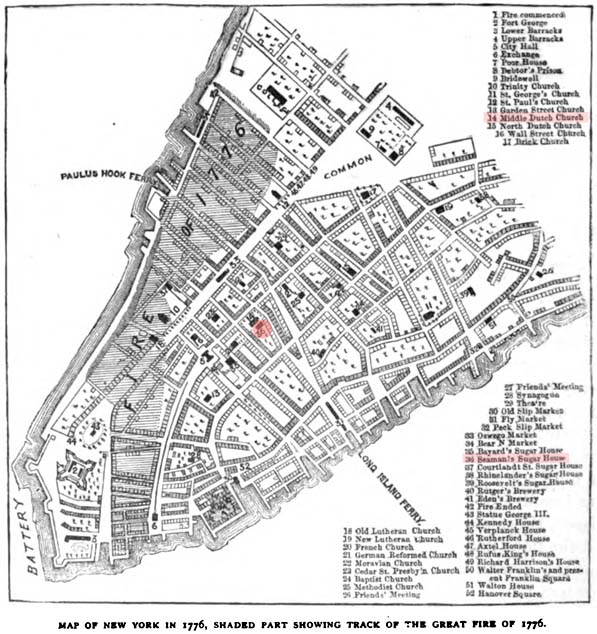

1776 Map of Lower Manhattan Showing Location of Livingston Sugar House (Pink Circle) and Extent of September 21, 1776 Fire on Manhattan Island. From the September 1889 Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. Edited by Mrs. Martha J. Lamb.

https://books.google.com/books?id=jbQTAAAAYAAJ&q=dutch+reform#v=onepage&q=%22middle%20dutch%22&f=false

Of these three, the Livingston family’s sugar house – likely the same Livingston family from which William Livingston, the Revolutionary War era Governor of New Jersey and head of the New Jersey militia descended – ended up becoming the most notorious. At some point it became known as the “Old Sugar House.” Built by the Livingston family in 1754, it was located next to the Middle Dutch Church between present day Nassau Street, Liberty Street (renamed in 1794 from its original name of Crown Street), William Street and what was Cedar Street (renamed from Queen Street).

The 1889 book “Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries” by Martha J. Lamb describes the Old Sugar House, “In Liberty Street, alongside the Dutch church, was the great ugly-looking sugar-house of the Livingstons, a gray stone building, six stories high, with immensely thick walls and small deep windows.”

The 1910 book “American Prisoners of the Revolution” by Danske Dandridge provides the following descriptions of the Old Sugar House during the time it was used as a prison:

… a dark, stone building, with small, deep porthole looking windows, rising tier above tier; exhibiting a dungeon-like aspect. It was five stories high, and each story was divided into two dreary apartments.

On the stones and bricks in the wall were to be seen names and dates, as if done with a prisoner’s penknife, or nail. There was a strong, gaol-like [i.e., prison-like] door opening on Liberty St., and another on the southeast, descending into a dismal cellar, also used as a prison. There was a walk nearly broad enough for a cart to travel around it, where night and day, two British or Hessian guards walked their weary rounds. The yard was surrounded by a close board fence, nine feet high. ‘In the suffocating heat of summer,’ says Wm. Dunlap, ‘I saw every narrow aperture of these stone walls filled with human heads, face above face, seeking a portion of the external air.’

While the gaol fever [i.e., Typhus] was raging in the summer of 1777, the prisoners were let out in companies of twenty, for half an hour at a time, to breathe fresh air, and inside they were so crowded, that they divided their numbers into squads of six each. No. 1 stood for ten minutes as close to the windows as they could, and then No. 2 took their places, and so on.

Seats there were none, and their beds were but straw, intermixed with vermin.

For many days the dead-cart visited the prison every morning, into which eight or ten corpses were flung or piled up, like sticks of wood, and dumped into ditches in the outskirts of the city.”

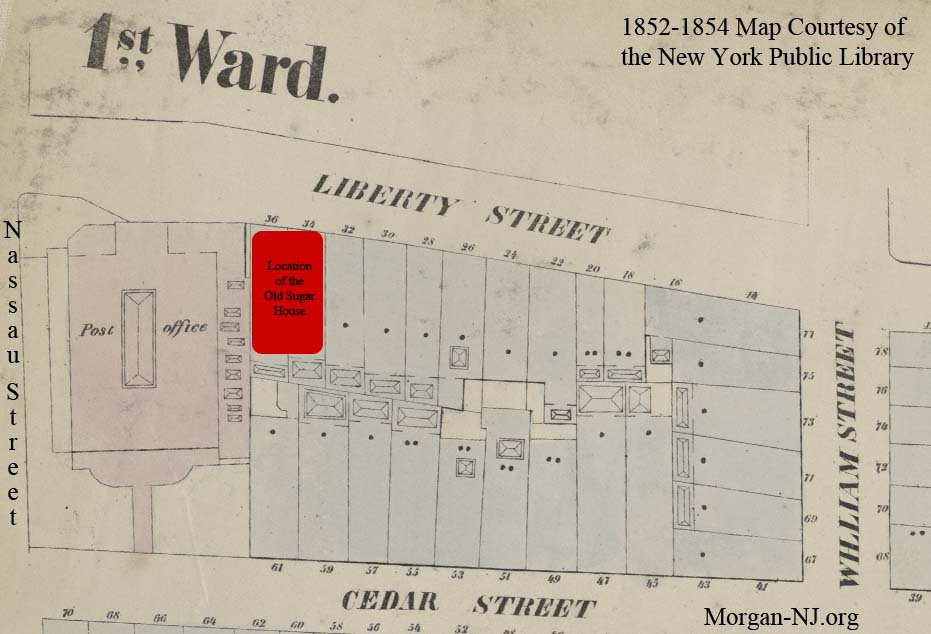

Map of Location of Livingston’s “Old Sugar House”, Circa 1852 – 1854

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. (1852 – 1854). Plate 4: Map bounded by Liberty Street, Maiden Lane, South Street, Old Slip, William Street, Exchange Place, Broad Street, Nassau Street Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-c7c7-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Lamb wrote further about the Old Sugar House in her 1889 book:

The British army found this great structure admirably adapted for the incarceration of their American prisoners-of-war, on taking possession of New York City in 1776. Each story was divided into two great rooms with low ceilings, into which were huddled the sick and the well, indiscriminately, thousands of them; and their captors had little else to furnish except iron bars for the windows, and chains to keep the poor suffering prisoners from walking about within their narrow confines. A ponderous jail-like door opened into Liberty Street to the court-yard, through which two British sentinels were constantly pacing night and day. On the southeast a heavy door opened into the dismal cellar used as a dungeon. The yard was surrounded by a close board fence nine feet high. The building was erected long years before for a sugar-refinery, and the genius of an enemy could not have fashioned it better as a place of torture. The prisoners taken on Long Island and at Fort Washington were the first to enter it. The coarsest food was doled out in scanty measure, and the men devoured it like hungry wolves or ceased to eat at all. During the winter months they had no fire or blankets, and in the torrid hear of summer almost no air to breathe. These victims were constantly decreased by death, and as constantly increased by newly captured patriots.

During this time period William Dunlap, future painter and theater producer, playwright, and actor, was a student in a school on Cedar Street, located across the street from the Livingston Sugar House. He wrote:

I went to school in Little Queen (now Cedar) street, and my seat at the desk, in an upper room of a large store-house kind of building, placed me in full view of the sugar-house corner of Crown (now Liberty) street and Nassau. The reader may have noticed the tall pile of building with little port-hole windows tied above tier. In that place crowds of American prisoners were incarcerated, pined, sickened, and died. During the suffocating heat of summer, when my schoolroom windows were all open and I could not catch a cooling breeze, I saw opposite to me every narrow aperture of those stone walls filled with human heads, face above face, seeking a portion of the external air. What must have been the atmosphere within? Andros’s description of the prison-ship tells us. Child as I was, this spectacle sunk deep into my heart. I can see the picture now.

1729 Illustration of the Middle Dutch Church Located at the Corner of Nassau Street and Crown Street (now Liberty Street) in Manhattan. From the September 1889 Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. Edited by Mrs. Martha J. Lamb.

https://books.google.com/books?id=jbQTAAAAYAAJ&q=dutch+reform#v=onepage&q=%22middle%20dutch%22&f=false

Lamb again regarding the Dutch Church next door:

The pretty Dutch church was in convenient proximity to receive the overflow. The pews were torn out and used for fire-wood during that first winter, and the whole interior disfigured, dismantled, and destroyed. A floor was laid from one gallery to another, and three thousand prisoners were accommodated. They were packed together so close they could hardly breathe, and the church became the scene of some of the most harrowing and tragic events in the annals of the country. The sufferings of that winter were scarcely less there than in the sugar house of the Livingstons, which ranked foremost in horrors among the sugar-house prisons, as the old Jersey prison-ship took precedence among its king upon the water. The inmates of the church were the following year transferred to other and the floor taken up and covered with tan-bark; the sacred edifice was thus converted into a riding-school for the training of dragoon horses. A pole was placed across the middle of the interior for the horses to jump over, and it was a noisy, rollicking meeting-place for British officers and soldiers until the end of the war.

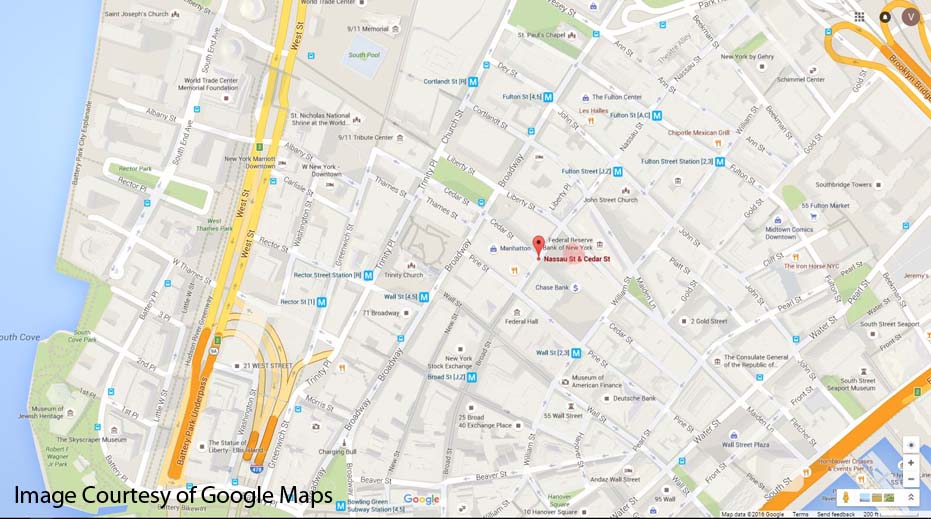

Map of the Location of Livingston’s “Old Sugar House”, on Manhattan Island (Pink Dot), Circa 2016. Map Courtesy of Google Maps.

Finally, Lamb sized up the situation in general:

New York City was severely humiliated during its occupation by a foreign foe. It was transformed virtually into a garrison town, all courts of justice were closed, trade ceased, there was no employment for laborers, provisions and fuel were scarce and extravagantly high, and the poor were in a perishing condition. The poisonous prisons on every hand were agonizing to the inhabitants. A few of the opulent citizens who took no part in the unhappy disputes tried to remedy evils, but military law prevailed, no communication was allowed with the captive patriots, and aid conveyed to them by stealth only doomed the benefactor to the same fate. When the victims confined in the Middle Dutch church crawled to the windows begging for food, a sentinel, pistol in hand, would turn back the gifts of the charitable.

It was into this terrible situation that James Morgan, Jr. was confined, at around 20 years of age and apparently for a year, before being exchanged. Thus far, specific records regarding the exchange have not been found by this author.

Again from Ann Morgan’s testimony of December 26, 1853:

That immediately on his return from captivity he [i.e., James Morgan, Jr.] again joined his father’s Company as Sergeant, and served until the company was discharged; That he then joined a company commanded by Lieu. Commandant Simon Van Wickle (who was declarant’s father) as an Ensign or Lieut; and served in said company one year; and that he was frequently afterwards in service as a volunteer until the end of the war; having served as she verily believes fully three years in the aggregate; one of which was as an Ensign, or Second Lieu, in the company commanded by declarants father as aforesaid; eighteen months, (including the time he was prisoner in New York) as a Sergeant in the company Commanded by his father, Captain James Morgan, as aforesaid, and more than six months as a volunteer private in other companies.

James Morgan, Jr.’s scar would likely have proven to be a daily reminder of his capture and harsh treatment by the British. A constant reminder when, some 35ish years later while serving as a member of the United States House of Representatives, he voted in favor for the War of 1812 against the British.

August 11, 1844 was the last day the Middle Dutch Church was actually used as a church. It was subsequently converted to a Post Office. As it continues to be to this day, Manhattan property stayed in great demand in the nineteenth century and thus the structure was itself demolished around 1880 to make way for the five story Mutual Life Insurance Building which opened in 1882. This building was itself demolished some 80 years later, along with part of Cedar Street, to make way for the a 60 story office building originally named One Chase Manhattan Plaza which opened in 1961. One Chase Manhattan Plaza was, in turn, renamed to 28 Liberty Street by the Chinese investment company which purchased it in 2013 (for $725 million).

The notorious “Old Sugar House,” located on plots 34 & 36 along Liberty Street in Manhattan, was torn down in 1846. More info about the Old Sugar House can be obtained from two New York Times articles; one from January 16, 1852 and the other from October 14, 1872.

Headstone of Ann J. Van Wickle Morgan, Second Wife of Major General James Morgan, Jr. in the Morgan Family Cemetery. Born: May 15, 1784. Died: Aug 13, 1869. Age: 85 Years, 2 Months, 28 Days. Image Courtesy of Chrissy Cislo.

Ann Morgan lived to the age of 85 years, 2 months and 28 days. She died, 15 years after giving her above testimony, on August 13, 1869, and is buried in the Morgan Family Cemetery in Morgan, NJ between her daughter Eveline [also referred to in some places as “Emmeline”] on one side, and her grandson and wife, James Rutus Morgan and Julia.

Thanks again to my college friend Valerie for letting me know her father Robert is a Revolutionary War aficionado; her father Robert for getting me connected to Noreen Bodman, Executive Director of the historical non-profit organization “Crossroads of the American Revolution;” Noreen Bodman who further referred me to another member, William Kidder; and finally to William Kidder for pointing me to the source of information regarding Ann Morgan’s application for the pension. Click here for William Kidder‘s short bio about the life of Captain James Morgan, Sr. in the Revolutionary Neighbors section of RevolutionaryNJ.org. Also checkout other places on their web site such as their Guided Tours.

Originally posted on September 18, 2016.